Where to draw the line as a product manager

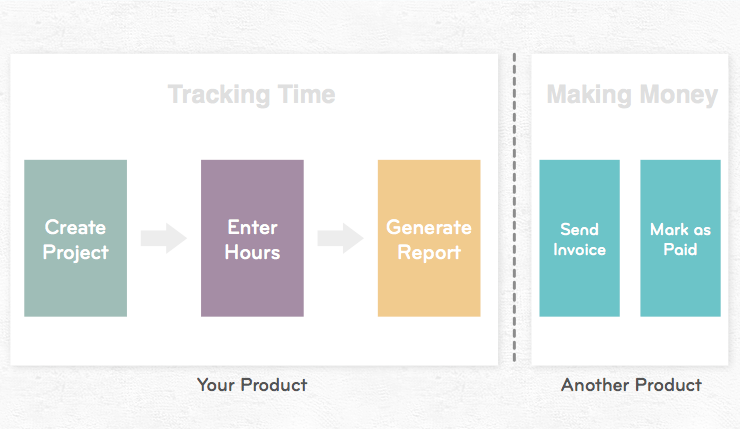

The most important thing a product manager does is decide where their product stops and someone else’s product takes over.

If an app does too little then it isn’t worth the cost of installation, or registration let alone the actual purchase price. Similarly if it does do too much, then it will clash with some other pre-existing software or workflow that users are already happy with. It’s a Goldilocks problem, you need to find the product that’s just right.

Example: Time tracking

At an absolute minimum time tracking is just totaling a list of numbers. Now, if that was all a web app had to offer, it would be useless. Excel or Google docs does that job already. It’s at this point we realise simplicity is overrated. No amount of web fonts, HTML5 transitions, or sound effects can help a product that simply isn’t earning its keep.

At a maximum, time tracking can involve project management, budgets, contractors, invoicing, receipt tracking and employee monitoring. Applications that incorporate so many surrounding tasks tread on the toes of products already in place, in this case, Xero, Ballpark, Basecamp, etc.

Products exist to solve problems that occur in a workflow. They have a start and end point within that workflow. To understand where these points should be, you must understand the entire workflow. Let’s look at the workflow for a team ordering lunch every day…

If you’re building an app that helps teams order lunch every day, the workflow might look like this…

- Someone gets hungry.

- He or she communicates this to the rest of the team.

- Debate ensures about whether to go out or order in.

- Second debate about where to order in from.

- Menus for different places are passed around.

- A decision is arrived at quickly

- One person is appointed to gather everyone’s orders.

- That person then places order.

- That person communicates delivery time & cost to everyone

- Time passes.

- Food arrives, and is eaten.

- Orderer checks if everyone paid enough & who still owes money.

- Finances are settled, or the settlement is postponed until tomorrow.

- Some will talk about the food on Twitter or Facebook. Some will post pictures on Instagram. Others will review on Yelp.

- Everyone returns to work.

When you understand the full workflow, you can focus on the most concise painful subset your product solves, or alternatively the piece you can make more fun or interesting. Don Dodge has a great article titled “Is your product a vitamin or a painkiller” that discusses the difference here.

Where should you start?

Start your product at the first step where you can add value. For our lunch example, this is probably step four. Starting any earlier would mean taking on chat products or email, rarely a good idea. (Side-note: Unstructured communication always falls back to email or chat. You can count on no fingers the amount of products who have changed this over the years.)

A real world example would be TripIt. TripIt solves travel management. Their app could start with flight search, but TripIt couldn’t add value there. The first point they can add value is right after a booking is made. By understanding the entire workflow, Tripit designed a great solution. The last thing that happens before TripIt can add value is “User opens booking confirmation”. This is the first point TripIt can add value, so they start with that email and import from there. Similarly, Instragram starts with importing your social network, or time tracking can start by importing projects from Basecamp. Good APIs and import features help your users get off to an easy running start.

Where should you stop?

Your budget, whether time or money, should restrict but never define your scope. A large budget should define how well a problem is solved, never how many problems are tackled. Attempting to tackle an entire workflow from start to finish for all types of users is near impossible.

Your product should stop when the next step:

- has well defined market leaders looking after it (e.g. PayPal, IMDB, Expedia), and you don’t intend to compete.

- is done in lots of different ways by lots of different types of users (e.g. trying to process salaries in a time tracking app would be tricky)

- involves different end-users than the previous steps (e.g. managers, accountants etc.)

- is an area you can’t deliver any value.

Identify and Eliminate Meaningless Steps

If a user is finished with your app and their next step is to download a file so that it can be emailed elsewhere, that’s a meaningless step. If it’s to export their expenses to CSV so that that file can be downloaded and re-saved as XLS then mailed to their accountant, that’s a meaningless step. If completing a project then means downloading all the files, zipping them and emailing them to the client for safe keeping, that’s a meaningless step. Emails are almost always a source of meaningless steps, in that they rarely carry enough information (“Someone posted a comment”), or they don’t link up the obvious actions (confirm, mark as resolved etc).

In general any time your user is clicking through a defined series of steps, adding no insight and making no decisions along the way, it’s a sign there are steps to be killed.

Future Iterations

Always fill in the gaps before expanding the product. The shift from shrink-wrapped to subscription software rewards products that are reliable and complete, not buggy and bloated. Expanding your product to solve a larger problem can work wonders, but can only be done on a solid foundation. If your fundamental product isn’t holistic, then adding more features only makes things worse.

So much is written about the pursuit of simplicity these days but often there is a confusion.There is a fundamental difference between making a product simple, and making a simple product.

Making a product simple emphasizes removing all unnecessary complexity so that every users can solve their problems as efficiently as possible. Making a simple product, however, is about scoping down and choosing the smallest subset of the workflow where your product delivers value. This MVP approach runs the risk of being labelled a point solution, or worse, “a feature but not a product”.

When shooting for a “simple product”, be careful where you draw the line.